The Last Goodbye

From the National Geographic October 2019 Issue: Vanishing. I began my career covering conflicts. Starting at 26, I found myself in places such as Kosovo, Angola, Gaza, Afghanistan, and Kashmir. My reason for going, I told myself, was to document the brutality. I thought the most powerful stories were those driven by violence and destruction. While the importance of shining a light on human conflict shouldn’t be minimized, focusing only on that turned my world into a horror show.

But slowly, as I covered conflict after conflict, it became clear to me that journalists also have an obligation to illuminate the things that unite us as human beings. If we choose to look for what divides us, we will find it. If we choose to look for what brings us together, we will find that too.

Those years in war zones led me to an epiphany: Stories about people and the human condition are also about nature. If you dig deep enough behind virtually every human conflict, you will find an erosion of the bond between humans and the natural world around them.

These truths became personal guideposts when I met Sudan, a northern white rhinoceros and, eventually, the last male of his kind.

I saw Sudan for the first time in 2009 at the Dvůr Králové Zoo in Czechia (the Czech Republic). I can recall the exact moment. Surrounded by snow in his brick and iron enclosure, Sudan was being crate trained—learning to walk into the giant box that would carry him almost 4,000 miles south to Kenya. He moved slowly, cautiously. He took time to sniff the snow. He was gentle, hulking, otherworldly. I knew I was in the presence of an ancient being, millions of years in the making (fossil records suggest that the lineage is over 50 million years old), whose kind had roamed around much of our world.

On that winter’s day, Sudan was one of only eight northern white rhinos left alive on the planet. A century ago there were hundreds of thousands of rhinos in Africa. By the early 1980s, hunting had reduced their numbers to around 19,000. Rhino horns, like our fingernails, are simply keratin, with no special curative powers, yet they’ve long been valued by people around the world as antidotes for ailments from fever to impotence.

When I met Sudan, the remaining northern white rhinos were all in zoos, safe from poaching but with limited success at breeding. Conservationists had hatched a bold plan to airlift four of the rhinos to Kenya. The rhinos, it was hoped, would be stimulated by their ancestral habitat’s air, water, food, and room to roam. They would breed, and their offspring could be used to repopulate Africa.

When I first heard of this plan, it sounded to me like something out of a children’s story. But I quickly realized that this was a desperate, last-ditch effort to save a species. Dvůr Králové Zoo, Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya Wildlife Service, Fauna & Flora International, Back to Africa, and Lewa Wildlife Conservancy worked hard to make the move possible. On a frigid December night the four rhinos left the Dvůr Králové Zoo in Czechia for Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya.

How did we arrive at the point where such desperate measures were necessary? It’s astonishing that a demand for rhino horn based on little more than superstition has caused the wholesale slaughter of a species. But it’s encouraging that a disparate group of people came together in an attempt to save something unique and precious, something that once lost would be gone forever.

Meeting Sudan in Czechia changed the trajectory of my life. Today my work doesn’t focus only on the human condition. Rather, I tell stories about nature, and in so doing, I tell stories about our home, our future, and the interdependence of all life.

Nine years after the airlift, I received a call to hurry to Kenya. At 45, Sudan was elderly for his species. He had lived a long life, but now he was dying. In his last years he experienced again his native grasslands, although always in the company of armed guards to keep him safe from poachers. And he had found stardom—he’d been affectionately dubbed the “most eligible bachelor in the world.”

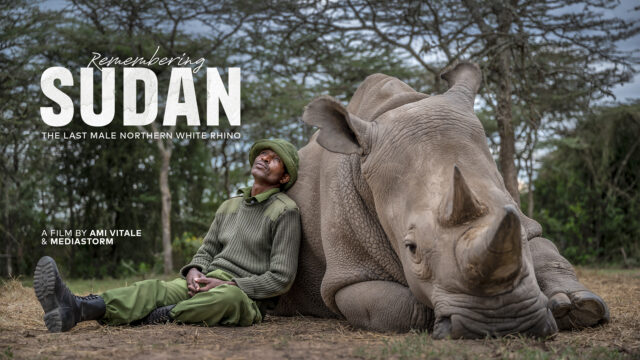

Sudan’s death was not unexpected, yet it resonated with so many. When I arrived, he was surrounded by the people who had loved him and protected him. Joseph Wachira, the man pictured with Sudan on the previous page and one of his dedicated keepers, went to give him one more rub behind his ear. Sudan leaned his heavy head into Wachira’s. I took a photo of two old friends together for the last time.

Those final moments were quiet—the rain falling, a single goaway bird scolding, and the muffled sorrow of Sudan’s caretakers. These keepers spend more time protecting the northern white rhinos than they do with their own children. Watching a creature die—one who is the last of its kind—is something I hope never to experience again. It felt like watching our own demise.

The northern white rhinos may not survive human greed, yet there is a tiny sliver of hope. Today only two females are left in the world, but plans are in place to try in vitro fertilization to breed them.

This is not just a story to me. We are witnessing extinction right now, on our watch. Poaching is not slowing down. If the current trajectory of killing continues, it’s entirely possible that all species of rhinos will be functionally extinct within our lifetimes. Removal of a keystone species has a huge effect on the ecosystem and on all of us. These giants are part of a complex world created over millions of years, and their survival is intertwined with our own. Without rhinos and elephants and other wildlife, we suffer a loss of imagination, a loss of wonder, a loss of beautiful possibilities. When we see ourselves as part of nature, we understand that saving nature is really about saving ourselves.

Sudan taught me that.

This photo of Joseph Wachira saying goodbye to Sudan and the photo of Fatu, Sudan’s Granddaughter and The Last Northern White Rhino on the Savannah are both available for purchase.

Loading Images